> Information Center > Technical FAQs > Protein Technology Column > How is phage display used to develop new proteinsPhage display is a laboratory technique for the study of protein–protein, protein–peptide, and protein–DNA interactions that uses bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria) to connect proteins with the genetic information that encodes them.[1] In this technique, a gene encoding a protein of interest is inserted into a phage coat protein gene, causing the phage to "display" the protein on its outside while containing the gene for the protein on its inside, resulting in a connection between genotype and phenotype. These displaying phages can then be screened against other proteins, peptides or DNA sequences, in order to detect interaction between the displayed protein and those other molecules. In this way, large libraries of proteins can be screened and amplified in a process called in vitro selection, which is analogous to natural selection.

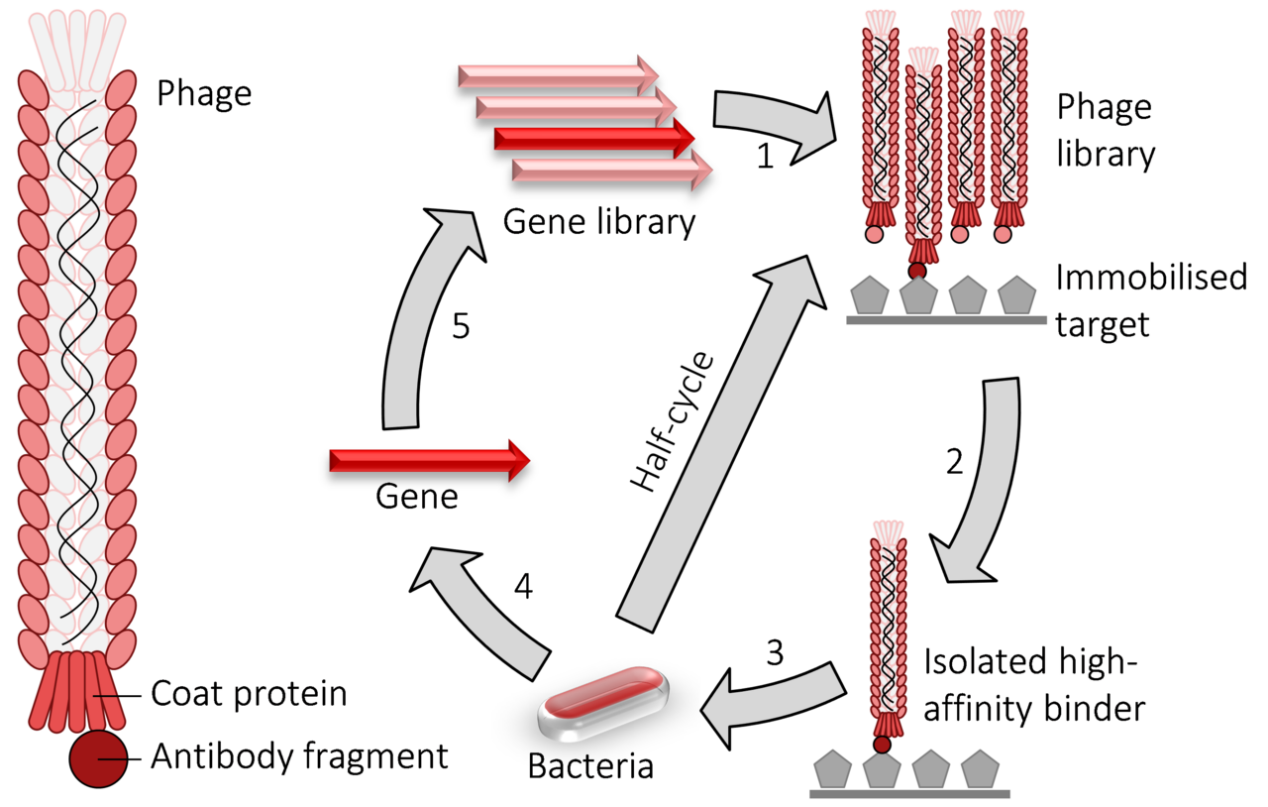

Phage display cycle.

1) fusion proteins for a viral coat protein + the gene to be evolved (typically an antibody fragment) are expressed in bacteriophage.

2) the library of phage are washed over an immobilised target.

3) the remaining high-affinity binders are used to infect bacteria.

4) the genes encoding the high-affinity binders are isolated.

5) those genes may have random mutations introduced and used to perform another round of evolution. The selection and amplification steps can be performed multiple times at greater stringency to isolate higher-affinity binders.

Like the two-hybrid system, phage display is used for the high-throughput screening of protein interactions. In the case of M13 filamentous phage display, the DNA encoding the protein or peptide of interest is ligated into the pIII or pVIII gene, encoding either the minor or major coat protein, respectively. Multiple cloning sites are sometimes used to ensure that the fragments are inserted in all three possible reading frames so that the cDNA fragment is translated in the proper frame. The phage gene and insert DNA hybrid is then inserted (a process known as "transduction") into E. coli bacterial cells such as TG1, SS320, ER2738, or XL1-Blue E. coli. If a "phagemid" vector is used (a simplified display construct vector) phage particles will not be released from the E. coli cells until they are infected with helper phage, which enables packaging of the phage DNA and assembly of the mature virions with the relevant protein fragment as part of their outer coat on either the minor (pIII) or major (pVIII) coat protein. By immobilizing a relevant DNA or protein target(s) to the surface of a microtiter plate well, a phage that displays a protein that binds to one of those targets on its surface will remain while others are removed by washing. Those that remain can be eluted, used to produce more phage (by bacterial infection with helper phage) and to produce a phage mixture that is enriched with relevant (i.e. binding) phage. The repeated cycling of these steps is referred to as 'panning', in reference to the enrichment of a sample of gold by removing undesirable materials. Phage eluted in the final step can be used to infect a suitable bacterial host, from which the phagemids can be collected and the relevant DNA sequence excised and sequenced to identify the relevant, interacting proteins or protein fragments.

The use of a helper phage can be eliminated by using 'bacterial packaging cell line' technology.

Elution can be done combining low-pH elution buffer with sonification, which, in addition to loosening the peptide-target interaction, also serves to detach the target molecule from the immobilization surface. This ultrasound-based method enables single-step selection of a high-affinity peptide.